Simon Berg, a sales manager for a multinational pharmaceutical company, has written and lectured extensively on the Dead Sea Scrolls. His book Insights into the Dead Sea Scrolls – A Beginner’s Guide (2009) provides a concise, scholarly overview of the subject.

.

“And even if we had an autograph copy of, say, the Book of Ezra, it would not answer all our questions, for it was created at a time (2400 years ago) when writing was imprecise – even before the invention of punctuation.”… Preface to the JPS Tanach.

.

Kings ll 22:8 And Hilkia the High Priest said unto Shaphan the scribe, “I have found the Book of the Law in the House of the Lord.” And Hilkiah gave the book to Shaphan and he read it.

Ibid. 23:2…and he (King Josiah) read in their ears (to all the inhabitants of Jerusalem) all the words of the Book of the Covenant which was found in the House of the Lord. This was 67 years after King Manasseh had systematically destroyed all the Torah Scrolls in the land. (1)

The background to this very moving event describes this book, believed to have been the Book of Deuteronomy, one of the five books of the Torah discovered in the First Temple. This took place 100 years after an invasion from the north by Assyrian Kings and the pillaging of the Temple which took place in 722 BCE. The description of King Josiah reading and learning about the contents the Torah for the first time, implied that the Jews had essentially abandoned their Judaism during this period, up to and including the eventual withdrawal of Assyrian influence from the Kingdom of Judah around 620 BCE. This date also implies that at least as far back as King Josiah, a written copy of the Torah existed in the First Temple, and about 650 years after the traditional date of the Exodus.

The Hebrew Bible, the Tanach, has only been in its final and present compilation and redaction for the past two thousand years. It contains twenty-four books divided into three sections: Torah (the so-called Five Books of Moses or Pentateuch), Nevi’im (the Prophets) and the Ketuvim (the Writings). The latter two sections make up the ‘nach’ part of the Tanach.

My objective is for the reader to question whether there are any differences in the Tanach (combination of Torah and nach) text of today, compared to the text from the Tanach in the Temple of Solomon, and I will also look at the balance of the texts and contents that make up the nach text on its own. Furthermore, I will present other versions of the Tanach and additional Holy Scriptures used by the Jewish people during the Second Temple era.

An essential criterion is for all of the Hebrew Bible and specifically the Torah, to establish that it is the original (Holy) text, word for word, letter for letter and all symbols, punctuation and column structure. In other words, there have been no differences and changes to the aforementioned criteria. In terms of the Hebrew Bible, what we thus read is regarded as being the original Hebrew or the Masoretic text, which was, and is the only text used by organized Judaism from the 1st Century on and after the destruction of the Second Temple.(2)

What we read and have accepted, for the past couple of thousand years, has been essentially due to our unquestioning faith. We believe that what is written in the Hebrew Bible is exactly the same as when it was originally received and composed. By now I’m sure you are wondering where I am going with this? So let me assure you that by the time you have completed reading this presentation, your faith or belief will have remained much the same, with however a greater insight to the meaning of the concept of original and Holy scripture. Scripture implies ‘holy’ text and the bible being the collection or canon of the works of scripture. Therefore there are different bibles for different religions.

Dead Sea Scrolls:

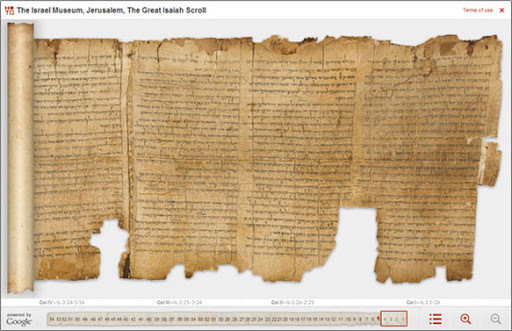

The biblical part of the Dead Sea Scroll collection found in the ruins of Qumran above the Dead Sea, consists of about 220 out of a total of 930 scrolls out of a corpus of 25000 fragments in varying lengths of completion. These were purportedly partly written by the Essenes residing there and the balance having been brought there from Jewish libraries mostly from Jerusalem. Only the one Isaiah scroll was in a complete form. All books of the bible were represented, some having around 20 copies of the same book or psalms. All, except for the Book of Esther and very little of Ezra/Nehemiah were found. These biblical scrolls dated mostly prior to the first millennium and perhaps as early as 250 BCE. They are thus the oldest known recorded biblical texts found. Interestingly, their contents were even older, as no doubt they were all copies of copies of much earlier scrolls. Before the DSS were found it was not a confirmed fact that the Masoretic text existed before the first century CE.

Professor Emanuel Tov of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, calculated that had all these biblical fragments been collated to complete sections of the Hebrew Bible, they would have amounted to ten compete Hebrew bibles - not that many, considering the Essenes were at Qumran for about 150 years in total.

Now this is where we come to the crux of the matter. Were they copies of copies? Whose copies? And critically how accurately were they copied? To provide the reader with some sort of time reference, the events at Sinai took place approximately 1330 BCE. So the earliest biblical Dead Sea Scroll could well have been a copy of a scroll dating back 1000 years from the ‘first’ Torah and 500 - 600 years after King David and in some instances only 300 to 400 years after some of the last prophets. The discovered copies of the Book of Daniel amongst the scrolls are believed to have been written during the actual early formation period of the Essenes (14) who wrote many of the scrolls.

In addition to many of their own legal text scrolls and other works directly associated with the Essenes discovered at Qumran, many are widely believed to have come from outside the region, mainly from Jerusalem. Thus the implication is that the scriptural / biblical scrolls discovered there, were to a greater or lesser degree also used by the Jewish people in the Kingdoms of Judea and Israel and later Palestine. Poignantly, there were basically similarly-varied copies of the biblical scrolls of the Tanach in usage outside Qumran, in addition to other holy scriptures used by the Jews. Some of these works we have long known about, for example the works of the Apocrypha and other religious works composed during the Second Temple times that were not eventually included in the Hebrew Canon. The Books of the Maccabees are another example. These works did not aspire to be Divine but rather to be inspirational during those critical times of persecution by the Romans and Greeks.

These ‘additional’ scriptures form collectively what is termed Pseudepigrapha. In addition to Apocryphal works there were about 600 other scriptural pseudepigraphic works that were used but not known of prior to the discoveries at Qumran. This is most probably one of the most significant outcomes of Scroll research, and fills the gaps previously left to speculation with regard to Jewish scripture, thought, prayer and observance.

Thus there were many, many variations of Judaism practiced and significantly differing from the practice and worship of Judaism today. The Judaism of the Pharisees which later became known as Rabbinic Judaism, is the essential and core Judaism of the past 2000 years. The development and inculcation of Sephardic, Ashkenazi and Lubavitch practices for example, still retain most of the basics of belief and are followed today. Thus the reader will begin to appreciate the significance of the word ‘Masoretic’. This word will come up time and again.

So, where is all this heading? Before I introduce the reader to some of the findings, I would like to add further intrigue by adding that only by about 850 CE did a final Masoretic text become established culminating with the Aleppo Codex, which will be covered further on in this paper.

Examples of some works are known as proto–Masoretic works i.e. related to, but some being abbreviated or variated sections from the Torah. Such works had additional wording in some verses that were used by some sects of Jews.

Some comparative examples from Qumran biblical scrolls vs. Masoretic:

Masoretic Genesis 1:19: “And God said, ‘Let the waters under the sky be gathered into one place, and let the dry land appear’. And it was so”.

Proto-masoretic: “And God said, ‘Let the waters underneath the heavens be gathered together in one gathering, and let the dry land appear’. And it was so”.

Masoretic Leviticus 3:11: “Then the priest shall burn these on the altar as a food offering by fire to the Lord.”

Proto-masoretic: “And the priest shall burn on the altar; it is the food, for a pleasing odour, of the offering made by fire to the Lord”.

In this example we also come across an additional insertion of other material following verse 24.

Masoretic: Numbers 27:23 – 24: “So Moses did as the Lord commanded him. He took Joshua and had him stand before Elazar the priest and the whole congregation; And he laid his hands upon him a charge, as the Lord commanded by the hand of Moses.”

Proto-masoretic: “And Moses did as the Lord commanded him; and he took Joshua the son of Nun, and set him before all the congregation; and laid his hands on him, and commissioned him as the Lord spoke by Moses”.

This shows that there were at least two editions of the book of Numbers circulating in Judaism during the Second Temple period.

Masoretic: Exodus 7:18 “The fish in the river shall die, the river itself shall stink, and the Egyptians shall be unable to drink waters from the Nile”.

Proto-masoretic: “And the fish in the dust of the Nile shall die, and the Nile shall stink, and the Egyptians shall wary of drinking water from the Nile.”

According to an analysis by Prof Emanuel Tov of the Hebrew University, out of 52 eligible Torah scroll texts, 46 were suitable for analysis. The outcome was that 57% of those texts followed the masoretic writing! To further break down: Masoretic Torah =2 4% and ‘other’ = 33%. (3)

The ‘Writings’ or nach portion of the Hebrew bible had a significant number of differences or variations. There were shortened versions of the Prophets; of note are the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah. However, were these two examples in fact simply shortened versions or actually two versions used at the time? This is a critical question and serves as one of hundreds of examples of the different texts that were in use during that period. Interestingly the Angelic praises in Isaiah 6:3 “Holy, Holy, Holy” is repeated twice and not three times as in the text we use today. This is seen in The Great Isaiah Scroll, an original Dead Sea Scroll discovered in Cave 1 and a copy of which is displayed in the Shrine of the Book of the Israel Museum. Multiple variations in wording are read in many of the biblical museum texts.

The Isaiah Scroll, designated 1Qlsaᵃ and also known as the Great Isaiah Scroll

There is now what is recognized to be a complete text missing from the end of the book of Samuel 1 chapter 11, that reappears in scroll coded 4QSam. This has now provided greater clarity for the events previously described. Remarkably the Jewish historian Josephus (37-100 CE) accounted the same details in his history of the Jewish People, the Jewish Antiquities. Psalm 145 was also discovered to have a ‘missing verse’ (4) between verses 13 and 14. A number of Christian Bibles have already made these changes or corrections to their latest editions.

So what could account for some of these numerous proto-Masoretic differences? The notion of an ‘original’ text was unknown to the people of this era. Each scribal copy constituted a distinct version of the text. This was probably due to composition-by-stages, as some of the scribes intentionally incorporated new material that helped interpret their own relevance to the text they were copying. Words could have been inadvertently omitted in the course of transmission. This is referred to as textual corruption, which could have occurred due to the scribe copying from a damaged copy. Possibly some words in the copy were illegible and replaced by words which were thought to be the correct ones.

In order to avoid this occurring during the Temple era, scrolls copied from a master copy named a “corrected scroll” or sefer muggah. For this purpose the Temple employed professional maggim or correctors. In addition, a second precise or corrected copy known as the “Scroll of the King” also existed; this accompanied the king wherever he went. (Deut. 17:18 19)

Prof James H Charlesworth of Princeton University, at a Biblical Archaeology Seminar held at St. Olaf College Minnesota USA, gave one of his lectures titled ‘Has our bible been copied accurately?” “This,” he said, “pre-supposes that there was therefore one original text, from which all others were copied.” According to Charlesworth, there was no one original or primary text. ”What we want is the least corrupt (distorted) bible, i.e. the earliest version, the earliest evidence.”

Targumim Onkelos and Jonathan

They are the Torah and the Prophets translated into Aramaic respectively in the early 2nd Century CE. In Talmudic times readings from the Torah within the synagogues were rendered verse-by-verse into the Aramaic translation. In many Hebrew Tanachim today, the Torah section has alongside it the Onkelos Aramaic translation. This is used when there were found difficult passages and it served to minimize ambiguities to assist with the understanding of the text. Onkelos was a Roman convert to Judaism. Following the return of many of the Jews from Babylon after their capture 70 years previously, Hebrew ceased to be the spoken language and was replaced by Aramaic.

Nehemiah was put in charge of rebuilding the surrounding wall of Jerusalem after its destruction and the return of the Jews from captivity in Babylon. During his time (+- 480 BCE) the majority of Israelites as recorded in the Bible (Nehemiah 8:8) could no longer comprehend or read Hebrew. Thus translations were necessary. The original Hebrew Tanach was translated into the Aramaic language of the time.(19) There no longer exist copies of these early translations, which were of an earlier dialect of the Aramaic language than that recorded by Onkelos. Today Aramaic still appears in the Yemenite Tanach in the books of Ezra and Daniel.

There were two other well-known bibles that were also in usage at the time:

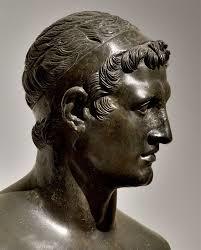

The Septuagint is derived from the Latin septaginta meaning seventy, or the abbreviation LXX. This is the oldest Greek version of the Hebrew bible originating during the friendly rule of Ptolemy ll Philadelphos of Egypt (285 – 246 BCE) for the benefit of the large Greek-speaking Jewish population of Alexandria, Egypt, who had become estranged from the Hebrew language. It helped the Jews to strengthen their religion and Jewish identity. It also allowed non-Jews to understand the monotheistic religion of the Jews and have access to Jewish Scripture. (18)

Ptolemy ll Philadelphos of Egypt

The Septuagint preceded the Dead Sea Scrolls regarding the Torah section in particular, with the nach section being completed over the following decades. The motivator was Demetrius of Phalerum, a statesman, philosopher and governor of Athens who had to escape to Egypt. There, he once again became prominent during the rule of Ptolemy 1 and later became one of the founders of the Great Library of Alexandra.(5) It was his suggestion that the ‘Law of the Jews’ should have a place at that library.

Legend has it that six scholarly elders from each of the twelve tribes were dispatched by the High Priest Elazar in Jerusalem, and over a period of 72 days completed the translation of the Torah, and later, having reconciled the differences by mutual comparisons, and submitted it to Demetrius,(6) Legend has it that all of the seventy two scholars came up with the identical translations. Prof Tov believes that the enterprise simply grew stage by stage, firstly as an official project and subsequently was continued by individuals. The actual Torah translation may have been under the auspices of the High Priest.

The Septuagint was not simply a literal translation. In many passages, the translators used terms from the Hellenistic Greek that made the text more accessible to the Greek readers, but they also subtly changed its meanings. Elsewhere the translations introduced Hellenistic concepts into the text.(7) To “set a cat among the pigeons,” there is the possibility that in fact the text of the Septuagint does reflect a more accurate translation, as it is older than the Dead Sea Scrolls! After the translation was read to the Jewish community, the leaders pronounced a curse on anyone who might seek to change it in anyway, since this was the authorized Greek translation of God’s Law. It later formed the “soil” from which Christianity grew and was used by the Apostles.

It remained for centuries a work on its own! It became a Torah not only to the Hellenized Jews of Alexandra but to the Jews of Palestine and later also the early ‘Christian Jews’. It was eventually rejected by the Jews with the rise of Christianity. Even today it is used in places as a ‘Targum’ to assist with the interpretation of words in the Torah. The Septuagint eventually became a complete Hebrew Bible. Later, additional works from the Apocrypha and other scriptural works originating from those Second Temple times (by Jews) became part of its canon, and are used by certain major Christian churches today. The books in the LXX are arranged differently from their position in the Hebrew Bible. Some fragments of the LXX were also discovered in the caves of Qumran.

It is interesting to note that Psalm 145 (referred to earlier) of the Masoretic text is written in anachronistic format i.e. the first verse begins with the letter A and the second with a letter B and so on. Except that a verse beginning with the letter nun or ‘N’ is absent. However it does appear in one of the psalm scrolls of the Dead Sea Scroll collection and in the Septuagint. This also applied to the missing verse from Samuel 1 Chapter 11 as appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls referred to earlier. The book of Jeremiah is approximately 5%-20% shorter than the Masoretic version and also appears as a different version.

Another example of differences between the Hebrew text and the Septuagint appears in Isaiah 7:14, where in the Dead Sea Scrolls and subsequent later Masoretic texts the words “Behold the young woman (Heb. Alma) will become pregnant and bear a son, and you will name him Immanuel”, a divinely inspired name. Yet in the Septuagint in place of the term “young woman”, the words were replaced by “virgin.” Christianity uses quotes from the book of Isaiah to endorse the coming of Jesus and the fulfillment of the prophecy, particularly as in this example.

The Samaritan Pentateuch

Extract: “The Samaritans separated (during and post the Babylonian exile of the Jews) themselves socially from the Jews, who in return shunned them.” Denied access to Jerusalem and recognition of not being halachically Jewish (Jewish legal law), Samaritan worship was centered on their temple on Mount Gerizim. This temple was razed to the ground around 100 BCE by the Jews for religious reasons. Then a system of worship was instituted by the Samaritans similar to that of the Temple at Jerusalem. It was based on the Torah possibly on copies that had been brought by Jewish priests that had left the Jerusalem temple for those on Mount Gerizim. Thus their Pentateuch was preserved among the Samaritans, which they read as one book and still used today.

Mount Gerizim, as it looked in 1900

The Samaritan Pentateuch is written in an early Hebrew script of the Samaritan alphabet, a direct descendant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet (a very ancient script used by the Israelites around the 6th – 5th Centuries BCE), which in turn is a variant of the earlier Phoenician alphabet. The earliest recorded Torah is believed to have been copied in this script.

Interestingly, some of the Qumran biblical manuscripts found were to be closer textually to the Samaritan Pentateuch than the Masoretic Torah. This is surprising, as the Samaritans were regarded as having separated or estranged themselves from the Jewish people at large. Comparatively, there are about 6000 differences to the Masoretic Torah. Also included is content is their law to build an altar on Mt. Gerizim.

Of the 6000 differences, 2000 are identical to those found in the LXX! From some recent biblical academic opinion arose the understanding that the differences to the Masoretic Torah are not a case of textual differences peculiar to the Samaritan version, but probably it is a Pentateuch in its own right and was the text of the day. It was not only used by the Samaritans and their descendants but was at the time also considered an authoritative Jewish text.

A comparison between the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Masoretic text shows that many of these differences represented a modernizing of the Masoretic text in terms of grammar and spelling in order that the MT could be better understood. (17)

It is still in use today by the Samaritans (who are not regarded as Jews) and have their annual Pascal lamb (Pesach) sacrifice on Mt. Gerizim. The Samaritan Pentateuch did not pose any threat to the Masoretic text, since it was described as falsification of the Jewish Torah. (7)

So far, I have demonstrated at least four Pentateuch, including those found at Qumran, showing variations to a greater or lesser degree, all of which were used by the different factions of Judaism during this very unstable period. At this stage, I again wish to point out that the concept of an original text was not likely to be considered of paramount importance.

Up to and immediately following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the final and recognized canon of the Hebrew Bible, the twenty-four books, had been fully established. The exceptions were “The Song of Songs” and Ecclesiastes that had not yet been accepted, but eventually they were also included. Only towards the end of that first century did it become finally redacted. This also meant that the Hebrew Bible had become standardized i.e. no variations subsequently were used or allowed. The subsequent regrouping of the rabbinical remnants from the Pharisees in Yavneh to debate the inclusion of certain books (8) into the canon, firmly re-established Judaism and all that it encompassed. This took place under Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkia in about 90 CE and is referred to as the Council of Jamnia (Yavne). It was then, that officially the Septuagint and Apocryphal books were rejected from the Jewish canon.

As the Jewish Diaspora began to spread both geographically and culturally, the threat of retaining, copying and using the same and ‘original’ bible throughout the Jewish world must have become widespread. With time and distance, there was no way of knowing whether the number of bibles all had exactly the same texts, with particular reference to the Torah itself. The concept of preserving the original biblical text first originated after the Jews returned from Babylon.

Whist I am not saying that categorically there were Torahs differing from each other, that element became recognized and eventually acted upon, albeit about eight-hundred years after the destruction of the Temple.

In the cities of Jerusalem and Tiberius 600 CE – 800 CE a group of scholars known as Masoretes took upon themselves to develop a system of checks and balances to ensure that the holy texts were accurately copied by scribes. Many of them were from the Karaite community and were excellent grammarians as well. In order to establish once and for all the ultimate template for the Hebrew bible incorporating Torah, Prophets and Writings, the Aleppo Codex was written. (11)

The Aleppo Codex:

A codex is a bound collection of hand-written pages which have the writing on both sides of the page as opposed to a scroll. Codices preceded books.

This codex became the official established text and later endorsed by the greatest Jewish sage Maimonides when using the codex in Cairo to reference his work the Mishnah Torah in the 11th Century and was designated the royal title Keter or Crown. The codex was first written by a Karaite Tiberian Masorete scholar Moses ben Asher and his son Aaron, who later in the 9th Century developed and added vowels to the text to ensure accurate meaning. It was recognized as the holiest Jewish work. It was written to be regarded as the most accurate version of the Hebrew Bible, both in words and spelling. Also, its layout in terms of paragraphs and style. It thus became the final template for the Hebrew Bible which is used to this day. In addition to developing a system of vowels, Aaron developed a series of musical cantillations (trop) to emphasize reverence to the words when being sung in the synagogues. During the Crusader invasion of Palestine 11OO CE the Codex was captured from Tiberius and ransomed. It was subsequently paid for and attained by the Cairo Jewish community.

In 1375 the Codex was transported back by a descendant of Maimonides in Cairo to Aleppo in Syria, where it was securely stored in a cabinet room of the synagogue for over 500 years, hence attaining its name. Immediately following the declaration of the State of Israel, the synagogue was destroyed. The following day only part of the original codex was found on the floor. That part of the Aleppo codex is now on display in the Israel Museum and has a history of intrigue that remains unsolved to this day.

The Leningrad Codex

The Leningradensis or the Codex of Leningrad is the oldest complete (Masoretic) manuscript of the Hebrew bible, written in 1009 in Cairo and now stored in the Russian National Library. (12) This codex used the Aleppo Codex and other scribal sources to ensure its accuracy. It was written two generations after the Asher codex by a scribe in Cairo, Samuel ben Jacob. The LC reflects the sequence found in Middle Eastern and Spanish manuscripts. The Writings were arranged according to the German tradition. For centuries it was kept out of circulation, being unknown to historians and Bible editors. (16) In 1840 a manuscript collector Abraham Firkovich acquired the codex. He sold it and other rare Jewish manuscripts to the Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) Imperial Library.

In 1987 an international team, led by the esteemed Professor Emanuel Tov, established proof-reading of the Leningradensis, culminating in what was considered then the most accurate updated version. It was published by the *Jewish Publication Society and is based on the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia mentioned below. Today it is available titled “JPS Hebrew – English TANAKH.”

The Stuttgartensia Biblia:

Together the above codices are known as the Asher Texts. Following these a new biblical edition, known as the Mikraot Gedolot, was published in Venice in 1516–17 by Daniel Bomberg. The second edition was edited by the Masoretic scholar Yaakov ben Haim of Leipzig in 1525. They were referred to as the Rabbinic Bibles and included commentaries.

The Stuttgartensia Biblia was used to translate the King James Bible into English. This bible, which was also known as the Biblia Hebraica Kittel was edited by Rudolph Kittel of Leipzig in 1906 and was identical to the Asher texts. A number of editions later it was renamed Biblia Stuttgartensia (13).

The fifth and revised edition was printed in 2020, and also included references and comparisons to recently released material from Qumran texts. The latest editions of the Mikraot Gedolot have been published, based directly on manuscript evidence, principally the Keter Aram Tzova (Aleppo Codex)(202), the manuscript of the Tanakh kept by the Jews of Aleppo. There are 21 volumes of the Bar Ilan Mikraot Gedolot ha-Keter, edited by Menahem Cohen(9). Also available today is Tanach Haketer/the Keter Crown Bible published in 2006 by Chorev Publishing House, Jerusalem.

I have covered a brief history of biblical textual variations from about 2300 years ago until the beginning of the second millennium. In 1956, the Hebrew University Bible Project was established to assemble every known textual variant of the Hebrew Bible. The project is designed to assemble variations, not to choose one that is correct. Yet none of these earlier versions pose any threat to the now established biblical text used today. Orthodoxy has the ability to look back and compare and cast aside texts they no longer deem accurate, and unequivocally devote themselves to scripts that are seen as Divine and original.

Thus in answer to the question posed in the heading of this article, the answer is “Yes.”

On the other hand, prior to the earliest known written recording of the Bible, we still have questions.

Summary:

- The framework of the Masoretic Text was already present in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

- 25 Scripture scrolls from sites other than Qumran (e.g. Masada, Bar Kochba caves) were also found to be identical to the Masoretic Text.

- This is as opposed to some of the Scriptural scrolls found at Qumran having variations of the biblical texts.

- Thus we understand that all the variations of the biblical texts found in the Judean Desert were regarded as being equally authoritative in ancient Israel in addition to those exclusively using the Masoretic Texts.

- All Scripture texts (outside Qumran) were equally authoritative in ancient Israel, except for the circles that created and perpetuated the Masoretic Text.

………………………………………

Notes:

1. The ArtScroll English Tanach Commentary 22:8 p593

2. My Jewish Learning Google

3. The Scribal and Textual transmission of the Torah… Emanuel Tov

4. The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls…Vanderkam and Flint p123

5. The Jewish Mind…Raphael Patai.

6. Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls… Vanderkam and Flint pp96–7

7. Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls…Lawrence Schiffman p212

8. Ibid, p162

9. Mikra’ot Gedolot “Haketer” project, founded and directed by Prof. Menachem Cohen, former Dean of the Faculty of Jewish Studies at Bar-Ilan

10. Scholars Seek Hebrew Bible Original Text…Anthony Weis

11. Crown of Aleppo…Tawil and Schneider pg.34

12. Ibid, p169

13. Ibid, p42

14. Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English…Geza Vermes pg. 11

15. The Scribal and Textual Transmission of the Torah…Emanuel Tov pg.59

16. JPS TANAKH… Jewish Publication Society. Preface pg.xii

17. The Text of the Old Testament, Peter Gentry

18. The Septuagint as a Translation, Matti Kuosmaane

19. Ancient versions of the Bible, Y. Younan-Levine

20. Aram-Tzovaha was a biblical city in modern Syria that was recently heavily bombed, and whose name was applied from the 11th century onward by some rabbinical sources and Syrian Jews to the area of Aleppo, in Syria. It is the same city that was conquered by King David’s General (Samuel II 8 verses 3-8) and known then as Hadadezer, ruled by King Tzovah. Aram of Damascus came to the assistance of the king but was defeated. Aleppo was also known in Arabic as Halabi where Abraham was purported to have milked his sheep to feed the poor.