Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. Trained as an economic historian, she enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. This article has been adapted from her obituary on Clive Chipkin that first appeared in the Heritage Portal on 16 January 2021 (http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/obituary-clive-michael-chipkin) and is reproduced here with the kind permission of same.

.

Clive Michael Chipkin, who passed away peacefully on 10 January 2021 at the age of 91, was an esteemed architect, architectural historian and heritage activist. A truly extraordinary person, he lived a rich and full life and meant much to friends and colleagues in the heritage and architecture communities.

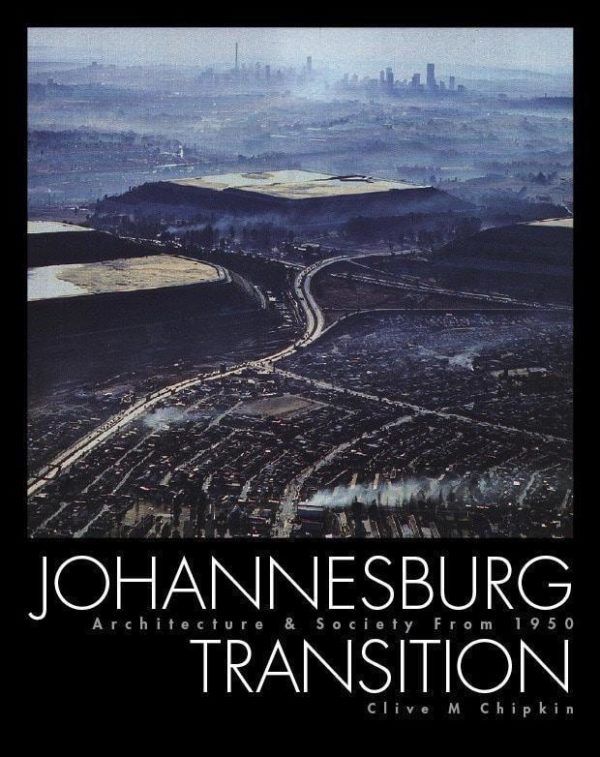

Clive was born on 21 March 1929 in Johannesburg, the city he made his own. His books Johannesburg Style: Architecture and Society 1880s to 1960s (David Philip, Cape Town, 1993) and Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950 (STE Publishers, 2009) are seminal monographs which made his name. They represent a lifetime of research, extraordinary knowledge and critical analysis. In 2013 his alma mater, the University of the Witwatersrand, recognized his scholarship with the award of an Honorary PhD.

Johannesburg Style quickly achieved iconic status and is regarded as a work of great distinction. Eric Itzkin, Head of Heritage in the Johannesburg City Council and author of Gandhi’s Johannesburg, describes it as a work of genius. The title, Johannesburg Style was meant to signify that Johannesburg has a characteristic way of doing things. Clive dissected how the colonial capitalist city with an entrepreneurial culture evolved – this was the unique style of Johannesburg.

The two Chipkin Johannesburg volumes give an understanding of the making and shaping of the city of Johannesburg’s and its cultural, social and historical underpinnings. They show a remarkable breadth of knowledge and the capacity to pose difficult questions about the roots of design and the shaping of architectural styles and fashions. How did international styles come to the city? For example, why and how did Brazilian architecture come to Hillbrow? These works are authoritative and commanding. Together they have set a high standard of serious scholarship in the study of architectural history in Johannesburg.

Clive’s lens was architectural history, but his breadth of scholarship was such that he enabled the reader to see the city and its buildings with a fresh understanding about why certain styles were adopted in particular periods and why the city has been rebuilt through successive waves of capitalist expansion. He was particularly enthusiastic about Modernist architecture in Johannesburg, because he was a product of the flowering and nurturing of those ideas at Wits in the forties.

The site of study is Johannesburg but the analysis of how and why a mining camp was founded in the 19th Century which over a century grew into a sprawling African metropolis and magnet for settlement is of international importance. Clive drew on a rich and diverse array of sources across architecture, politics, economics sociology and history to explain the development of the city through 120 years. Sources were meticulously collected, annotated, indexed and filed in a huge personal archive. Both books were superbly illustrated and some drawings were his own.

Clive’s work generated a great deal of interest and introduced a new and serious approach to the study of Johannesburg and its architecture. These studies have been a stimulus to further work among younger scholars in architectural history. His work has been compared to the best of architectural and social history of other cities, such as London and Berlin and been recognized among the best of urban history. Everyone quotes Chipkin. Johan Swart of the University of Pretoria told me he consulted his Chipkin volumes virtually weekly. Clive was a contributor to special Johannesburg editions of ADA 14 (1996) and Bauwelt (Berlin, 1997). SABC 3 created a two part TV documentary series in 1997 on Johannesburg Style. His readiness to participate in public debate about architecture and his ability to educate a broader public has strengthened a critical appreciation of heritage as expressed in the built environment.

What was the background to the making of Clive Chipkin that enabled him to write these two books?

Clive Chipkin leading a tour of the Ridges of Johannesburg for Brown University students, 2018 (Kathy Munro)

A Yeoville Childhood and School Education at KES

Clive was born in Johannesburg in 1929 in a semi-detached house in Yeoville-Bellevue at 116b Francis Street. He later lived with his parents at number 8 Bedford Road. The year of Clive’s birth was the year of the “Great Stock Exchange Crash” in the USA that preceded the world wide Great Depression of the thirties. Clive knew about economic anxiety as a child as his father lost his job and had a hard fight back to financial security. Throughout his life he carried an awareness of the impact of hardship on people’s lives. This concern explained his desire for a more equitable society. He always showed compassion to the less fortunate who he encountered. He would give regular handouts to the disabled beggar at the Hyde Park Corner traffic lights and had a string of regular beggars in Parkview who relied on his support.

Clive lived in Yeoville until 1949, later contributing a delightful reminiscence to the book, Politics and Community-based Research, Perspectives from the Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg (edited by Claire Benit Gbaffou, et al, Wits University Press, 2019). He described Yeoville as “a lovely middle class suburb, little detached houses, with verandas that faced the street and people, a lot of social life occurred on the veranda, you sat on the stoep and watched the street.” Clive remembered Yeoville as much more rural and that at his grandmother’s house at 93 Francis Street, although there were no longer any horses or carriages, there were stables on the property; survivals from a past age.

Of his high school, King Edward the Seventh (KES), Clive described it as “Edwardian in architecture; Edwardian in ethos; and Edwardian in education“, reflecting, “it was no surprise that I later took easily to deciphering Edwardian architecture and Imperial ethos”. He took great pride in his old school and what it represented.

Old photo of KES (SA Builder Magazine)

Clive related that he found a small pile of late 1930s copies of the S A Architectural Record on his father’s bookshelves. This this gave him his first glimpse of Modern Movement Architecture in the Transvaal and about that time the erection of a new block of flats, Radoma Court designed by architect Harold Le Roith, gave him an awareness of the then new international movement dropped into the middle of Yeoville-Bellevue. He later said, “it was not a damascene moment”, but he realized change was happening as economic recovery and a new optimism remade the Johannesburg of the 1930s.

The Architecture student at Wits

In the post-war years Clive went on to study architecture at Wits. He said he took some time to figure out what architecture was all about and more importantly how it related to the wider world. This was not always apparent from lectures. Clive was a curious student and university gave him the opportunity to audit lectures in other disciplines far removed from architecture but he looked for connections in disparate ideas and grew through asking unorthodox questions. Interrupting his studies in architecture, he took the route of combining study and work for a period, working for a builder and gaining practical experience under a Scottish foreman. Later, in 1954 he later joined Bernard Janks’ architectural practice, where he was one among many juniors. Here he met Alan Lipman, who took him in a new direction by asking Clive to sign the Stockholm Peace Accord and offered a political education in Marxist ideology. Clive said “some of it stuck". He returned to Wits and completed his degree in 1954 with a thesis on housing.

The Young Architect at Wayburne and Wayburne and his travels to England, Europe and India

In 1955 Clive began working in the Wayburne and Wayburne architectural office in the city. He became a friend of Lionel ‘Rusty Bernstein’ who, with Bram Fischer, helped draft the Freedom Charter. Clive remembered 1955 as the year of the Congress of the People in Kliptown - it was another education and a political influence in his life. He recalled that his finest architectural contribution was the ablution block he designed for the event.

In 1957, Clive achieved his professional membership of the Royal Institute of British Architecture (ARIBA) in 1957. The previous year, he had attended the Congress Internationaux D’architecture Modern (Summer School) in Venice. In 1956-7 he gained experience abroad when he worked for the London County Council.

Clive then set out to travel through Europe, hitch-hiking through the continent and afterwards travelling to New Delhi. There he discovered the making of imperial architecture of Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker and drew the connections to the architectural vision behind the Baker designed, Union Buildings in Pretoria. Returning to South Africa, Clive then wrote about India in his early article for the S A Architectural Record. The Indian sojourn influenced Clive’s thinking; he realized that the links between imperial cultures resulted in a cross fertilization of ideas in architecture and society. He talked of the fragrances of India and East Africa remaining with him.

Early view of the Union Buildings, Pretoria

First architectural practice

In 1958, Clive opened his own first practice at 302 Hollandia House Johannesburg. Initially it was a tiny largely struggling practice. He described it as being “overworked and underpaid”. Over time, the practice handled larger scale industrial and merchandising buildings, major development programmes, apartments and office blocks, central facilities buildings, clinics, houses, and historical buildings. Clive designed University Gate flats in Braamfontein in 1960. He worked for Trident Steel Company as a commissioned architect but ultimately chose to drop this association when new owners took over the company.

The firm was engaged in the overall industrial planning at Cape Gate, and designed a series of industrial and social amenities buildings at Vanderbijlpark (1984-1998). He enjoyed an excellent more than ten year association with this firm and had a close working partnership with Isaac Joffe. It was a period characterized by productive outcomes and a wonderful team spirit. Leadership Magazine of August 1991 described the work of his mature practice as supplying “socially responsive amenities, one of vision and hope”.

A Man of the Fifties and Architects against Apartheid, 1986

At the memorial service for Clive, his son Ivor described him as a “fifties man”, full of hopes for the remaking of the post-war world. He had retained that attitude of optimism and hope for good changes ahead in society at large and in the remaking of his city through architecture.

Clive’s practice both rejected and contested apartheid and never participated in any government, provincial or municipal work during the apartheid era (1948-1994). This mirrored his own values. In 1986, he was a founding member of the group “Architects Against Apartheid” (see Architecture SA, March/April 1994 p 17-18) an informal pressure group that challenged their colleagues to support radical changes to the Architects’ Act of 1970 and the Code of Conduct of the Institute of South African Architects. This group, that included architects such as Chipkin, Hans Schirmacher, Henry Paine, Ivan Schlapobersky, and Lindsay Bremner among others, tried to make colleagues aware of how the gross application of apartheid ideology to architecture was distorting the moral and ethical basis of the profession in South Africa. Clive was co-author of the Declaration of Human Rights (1986) relating to the architectural profession which resolved that it was unethical to participate professionally in the design and planning of apartheid buildings. Although their resolution to a special meeting of the Transvaal Provincial Institute of Architects was dismissed, many members of the group subsequently faced harassment and surveillance.

After 1994, he was responsible for the design of two South African Police Service buildings commissioned by the Department of Public Works – Boipatong (2001) and Mooifontein (2003) and for works of restoration in Heidelberg. In addition, his practice designed numerous low-cost rural houses on a pro bono basis and provided extensive honorary professional services in housing. His heritage work ranged from the renovation of Edwardian buildings in the 1960s to Inanda House, Illovo (1999). He has been a consultant for renovation work at the University of the Witwatersrand and to inner city renovation programmes.

Inanda House (High Street Auction Company)

Author and Scholar

Clive began his writing about architecture in the fifties. Three particularly noteworthy articles came out of his travels to India: New Delhi (Nov 1958), Chandigarh (Dec 1958) and India Dec 1959), all published in the South African Architectural Record. There were other important articles such as Baroque Background (Sept 1962); The Diffusion of Victorian and Edwardian Architecture (Jan. 1964 and Feb. 1964) and Beyond the Cape (March/April 1985) . (Also all published in the S A Architectural Record). Some of these articles anticipated his approach of using comparative analysis of methods and styles across continents and cultures. He was the author of more than 50 papers and articles.

In 1972 Chipkin contributed to the major heritage and architectural study of Parktown (Parktown, 1892-1972, a Social and Pictorial History – coordinated by Helen Aron with substantial contributions from Arnold Benjamin (later the author of Lost Johannesburg, 1979), Clive Chipkin and Shirley Zar, published by Studio Thirty Five Publications, 1972). Of that wonderful group of collaborators only Shirley Zar remains with us. It was a landmark portfolio of photographs of a disappearing Parktown and a book of essays that was the start of Clive’s major research on Johannesburg.

Clive recently completed an article on Parapet Houses and the Rondavel in Africa and this contribution will be published in a new Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World (Bloomsbury Press) edited by Randall Bird in 2022. He has also generously written an essay on interpreting the architect, Hermann Kallenbach’s three known rondavel houses in Johannesburg. This will be included in my upcoming biography of Kallenbach.

Satyagraha House designed by Herman Kallenbach (The Heritage Portal)

Valerie Francis Chipkin as Clive’s partner in life and in the creation of an archive

In his years of writing and research, Clive was assisted by his wife, Valerie Francis Chipkin (nee Krain) and together they created an impressive archive. They were married from 1959 until her death in 2015. She was the original mind behind organising the archive. The couple had three children: Peter, Lesley and Ivor. One interesting sidelight was that Clive and Val came close to purchasing the Rex Martienssen modern movement house (designed in 1940) in Greenside filled with Le Corbusier elements. Clive wrote extensively about the pioneering architect of the Modern movement in Johannesburg and his house in Johannesburg Style (see pages 181-184). But Valerie decided that an iconic house that could not be altered for their own family needs was not for them.

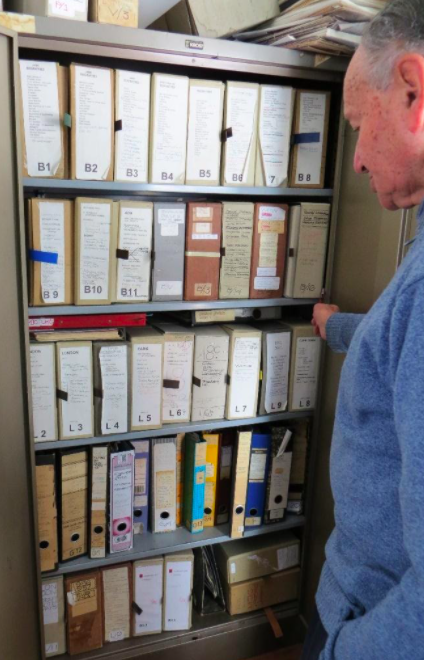

In 2015 Clive donated his research archive to the University of the Witwatersrand. The archive room was named the Valerie Chipkin Archive. An exhibition based on his archive and curated by Sally Gaule was first assembled and mounted in 2016, but that effort was put aside because of the Fees Must Fall campaign. It was upsetting to have to take down an exhibition that could have no visitors at that troubled time on campus. In fact we even thought of an online opening to save the exhibition - a prophetic anticipation of our new zoom culture! 2017 saw a fresh start and a new exhibition, was set up in March 2017. The opening event was a triumphant moment as Clive’s own intellectual home, the School of Architecture and Planning at Wits University, honored him with a celebratory event on the 22nd March 2017, one day after Clive’s 88th birthday.

During the last few years of his life Clive held a Visiting Research Fellowship in the School at Wits. He was warmly welcomed by the school to work in the library and return to his own archive. The gift of the archive to Wits was an extraordinarily generous gesture but also part of preserving the legacy of the City. The Wits architectural archive has expanded in the last six years. It has also received donations of archives from the late Anthony Lange, the late Brian Altshuler and Neil Fraser, now retired to Montagu. The archives of the late Gerald Gordon will also be coming to Wits.

Clive Chipkin and his archive before removal to Wits

Chipkin as tour guide to the Witwatersrand ridges of Johannesburg, 2018

Clive was a Johannesburg man all his life. Over nine decades he closely and critically observed a changing city and wrote about and interpreted the city with a fondness and a personal love of place. He argued that the cycle of creation, destruction and renewal in the city was part of a natural order. The city evolved at its own pace; the city had its own dynamic. His task was to document the architecture and architects and to pin down the stories of the people who with their vision, entrepreneurship, capital and energy turned a mining camp into an African metropolis. He was a sharp minded heritage critic and never allowed nostalgia to cloud his judgment.

He loved nothing more than expeditions to find out what had happened to specific buildings and suburbs. Clive led an unforgettable tour of the ridges of the Witwatersrand Ridges of Johannesburg for a visiting group of American students in August 2018, and this later became a special tour for the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. Each participant received a copy of Clive’s hand-drawn maps of the Ridges we visited and the route followed. These watercolour maps were specially crafted by Clive for these events. They are now a charming and unique memento of Clive and his city.

Clive wanted to explain the location of Johannesburg in relation to its geography and its topography. He always felt the ridges of the city are unique and it was his dream to celebrate the spectacular view sites of Johannesburg with a series of stunning Johannesburg celebratory large art work, blue plaques and story boards. He reminded me to look again at the broad sweep of the landscape of the city from each of the compass points. He was also very conscious of the much earlier, Stone Age inhabitants of the Melville Koppies and the Linksfield Ridge. Clive admired the work of the archaeologist, the late Revil Mason and wanted to raise awareness of the continuity between pre–history and history.

Johannesburg skyline from the east (Heritage Portal)

In 2015 Clive wrote a sensitive essay for the book The Johannesburg Gasworks (edited by Monica Lauferts and Judith Mavunganidze , published 2015 by Fourthwall books). Again it was another landmark piece of writing. He was also commissioned by Tsica Heritage Consultants in 2016 to document and advise on the history of and the future for the heritage buildings found within the orbit of the Corridors of Freedom route, a renewal and densification project of the City of Johannesburg. He worked with Monica and Judith and his report contains some of his ideas about ideal quality housing types for the renewal of old Johannesburg. In 2016 Clive also contributed to a Johannesburg Heritage tour, Cathedrals of Industries in 2016 when we devised a tour to cover New Doornfontein, inner city banking, the classic modernist Lion Match Factory in Industria and the very English Gas Works abutting Auckland Park (a classic item of industrial archaeology).

It was a joy to be with Clive on jaunts to track Cape Dutch gabled houses in Saxonwold and to mourn the ruin of a Leith house that had fallen to fire in Parktown. We walked his Yeoville, explored the Obels building, Beacon Royal and tracked down the Le Roith apartment blocks. Clive was enthusiastic and supportive when I found the 1913 Yeoville Water Tower blueprint and encouraged me to acquire this treasure, research and write about the Tower (he was quite happy for me to give the Tower a new date and provenance). He put me on to finding the origins of the meccano-like steel construction in Dortmund and recognizing the German firm, Aug. Klönne as the designer. When the Grand Station Hotel was lost to fire, we ventured out to inspect the damage and meet the people who lived there and now lost their homes and possessions. The building’s blackened shell was no longer grand and no longer a station hotel, but Clive peeled back the layers of history and went on to tell me all about the parallels between the Jeppe Station (across the road) and the London underground stations of the 1930s and the work of Charles Holden. We studied and traced the history of the series of three Shell Oil Company office headquarters. Clive gave me his personal experience and his take on the city and its evolution.

Clive was always generous in sharing knowledge and sparkled with curiosity and lively conversation. He was the most wonderful friend – compassionate, kind, funny, a great conversationalist as we bounced ideas off one another. I feel privileged to have been mentored by Clive and to have enjoyed his friendship from the time we met when his second book was launched at Boekehuis, Melville in 2009.

Yeoville water tower (Heritage Portal)

Marcia Leveson pays tribute to Clive: “Clive was always an adventurer and discoverer. We explored so much and he taught me so much – so many different and varied Joburg suburbs, the surrounding areas – off-beat places, Magaliesberg and surroundings and in Cape Town - my home town – he showed me aspects like the Egyptian influence that I had never noticed before, and I was able to introduce him to things I knew. He was always ready for a climb, a scramble, a hike, a new place to explore. He was a teacher, learner, and sharer. We shared other adventures by our endless conversations on every subject, not only architecture, our shared sense of humour and empathy, our crazy fun together. He was endlessly and massively supportive – not only to me but to everyone.”

Clive as the teacher and mentor to architects of the City

Clive was a mentor and friend to many architects - Fanuel Motsepe, at the memorial event paid tribute to the education Clive gave him. The architecture and heritage communities have lost a giant of a colleague whose career as architect and historian of the city spanned seventy years. A number of tributes have come in from architects who worked with Clive or were mentored by him or came to know him as a friend – Henry Paine, Heather Dodd, Marcus Holmes, Brendan Hart, Yasmin Mayet, Hannah Le Roux and Brian McKechnie, among others.

At the time of his passing Clive had completed a third volume, Johannesburg Diversity. The manuscript is under discussion with a prospective publisher. In this final volume to complete the trilogy, Clive wanted to draw together the many reflective threads of a lifetime both as an architect and scholar. The new book is also very visual; it is a pictorial record and interpretation drawn from his impressive archive. We hope that this book will be published in 2021.

Clive is survived by his three children, Peter Chipkin, Lesley Hudson and Ivor Chipkin and their spouses, Jelena and Carol and the grandchildren - Daniel, Liat, Noa, Rosanna and Sarah. Peter Hudson, husband of Lesley who passed away suddenly in 2019, was a very dear friend of Clive. Clive is also mourned by his close companion Marcia Leveson.

Thank you to Ivor Chipkin, Lesley Chipkin, Marcia Leveson, Sally Gaule and Keith Munro for their input and comments.

Sources

- Chipkin, C. 1993. Johannesburg Style: Architecture & Society 1880s – 1960s. Cape Town: David Philip.

- Chipkin, C. 2009. Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950. Johannesburg: STE Publishers.

- Chipkin articles in the S A Architectural Record and Review

- Chipkin, C: Essay in the Johannesburg Gasworks edited by Monica Lauferts and Judith Mavunganidze (published 2015 by Fourthwall books)

- Chipkin, C Appendix A Historical Overview of the Corridors of Freedom - attached to the Heritage Impact Study

- Chipkin, C.: “Preparing for Apartheid” in the publication Architecture of the Transvaal (UNISA, 1998, edited by Le Roux and Fisher) and a further chapter,

- Chipkin, C.: The Great Apartheid Buildings Boom to Blank Architecture, Apartheid and After (editors: Judin and Vladislavic) published by Nederland’s Architecture Institute, 1998.

- Citation for an Honorary D Arch 2013, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

- Mike Alfred Interview with Clive Chipkin 2004 – “No Coherence” - published on The Heritage Portal 1st March 2020

- I Schlapobersky, Henry Paine, Clive Chipkin, “Architects against Apartheid” - Architecture S A, March- April 1994

- Opening of the Valerie Chipkin Archive and Exhibition at the University of the Witwatersrand, February 2017 – Clive’s notes for his speech. - original mss.

- Le Roux, H. ”The Congress as architecture modernism and politics in the postwar Transvaal“– published in Architecture South Africa, Jan/Feb 2007, pp72-76 and also accessed via Wits Wired Space - mention made of Clive Chipkin and Rusty Bernstein friendship.

- Benit Gbaffou, C, Charlton, S, Didier, D, Dormann, K (Editors) 2019. Politics and Community-based Research, Perspectives from the Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Johan Lagae: Chipkin Makes sense of Jo’burg’s complex vision – interview with Chipkin in the Mail and Guardian, 19/07/2013