Irwin Manoim is a researcher attached to the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at UCT, with an interest in exploring neglected aspects of South African Jewish history. This article is an extract from a chapter exploring Jewish attitudes to apartheid, from his recently published book Mavericks Inside the Tent, a history of the Progressive Jewish movement in South Africa and its impact on the wider community (reviewed by David Saks elsewhere in this issue) An exhibition based on the book will be held at the SA Jewish Museum in Cape Town towards the end of this year.

On a Tuesday afternoon in early May this year, Rabbi Andre Ungar, aged 90, settled down for his afternoon nap. He never got up, dying peacefully in his sleep. Due to Covid19 lockdown regulations in New York, where he had retired, only three people were allowed to attend his funeral, not even a minyan.

Rabbi Ungar has been largely forgotten in South Africa, where he served a brief, but stormy tenure as rabbi of the Reform congregation in Port Elizabeth more than sixty years ago. But his death provides a useful occasion to recall his role here, because his story lays bare the ambiguous and conflicted attitudes of South African Jews during the early apartheid era.

***

A few months after Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, Julius Weinstein, president of the SA Zionist Federation told the movement’s 41st congress that South African Jews had always been in the forefront of the struggle against apartheid.[i] This opinion went down well at the conference, but was not universally shared. Rabbi Richard Lampert, himself a victim of police harassment, remarked that “The Jewish community developed a conscience on the day after Mandela was released.”[ii] The political analyst Steven Friedman, writing in Jewish Affairs near the close of the apartheid era, said: “Most of the time, with a few honourable exceptions, no Jewish leaders – religious or communal – gave any public indication that events in South African society as a whole concerned them … The silence was sharply ironic, since for much of the time Jewish leadership nominally represented a community justly perceived as a source of active anti-apartheid sentiment.” [iii]

Gideon Shimoni, in his book Community and Conscience[iv], usefully summed up the issues that confronted Jewish South Africa. A despised and persecuted minority in Europe, they fled to South Africa. Despite confronting local anti-Semitism in a fervently Christian society, they became an accidental part of the privileged white caste, narrowly escaping being classified as “Orientals” along with the Muslim merchants who were migrating to South Africa at the same time.

Many of the Jewish emigres had been involved in radical, anti-Tsarist politics in Eastern Europe. They continued to identify with radical politics in South Africa. Jews were disproportionately strongly represented among anti-apartheid activists, a point frequently made by hostile authorities. But the most outspoken, committed and courageous of the Jewish anti-apartheid activists were largely secular, operating outside the organised Jewish community.

Over the years, a number of rabbis spoke out against racial discrimination, some more loudly than others, but they were very much a minority. The community itself was often split, between those who spoke out, and those who remained silent, some arguing that speaking out would inflame anti-Semitism.

The Jews in South Africa were unusual in that, despite being accorded the privileged badge of whiteness, they never quite belonged. As Milton Shain and others have demonstrated, both English and Dutch administrations discriminated against the Jews.[v] Dr DF Malan’s National Party was loudly anti-semitic from the moment of its birth, explicitly excluding Jews from party membership, and driving the legislation that kept Jews out of the country. The party’s polemical anti-semitism quietened down after the Holocaust made such sentiments politically imprudent, but a low-key anti-semitism continued.

Nonetheless, there is also no denying that the Jews, whether loved or unloved, benefitted from apartheid’s bounties much as other whites: they could buy and sell property, live in comfortable suburban homes, own businesses, earn good salaries, vote in elections or run for political office, send their children to better schools and universities, enjoy the benefits of superior medical facilities, golf clubs, hotels and beaches, and never have to fear a police pass raid or sit on the hard benches of a third class train carriage. [vi]

The case of Rabbi Andre Ungar

An interesting illustration of the tensions between liberal and conservative factions of the Jewish community, between rabbis and their congregants, and between Jews and the outside world, can be found in the case of Rabbi Andre Ungar, the only rabbi to be deported from South Africa.

Ungar was born in July 1929 to a prosperous Modern Orthodox family in Budapest.[vii] Ungar’s pleasant suburban childhood came to an abrupt end with the Nazi occupation of Hungary, late in the war. The Jewish population were rounded up; in a single bloody year their numbers were cut down from 800 000 to 160 000. The Ungar family hid away under false identities in a non-Jewish part of town. The horror of Nazism, witnessed at first hand, would colour Ungar’s attitudes for the rest of his life. [viii]

He was selected to join a group of Eastern European teenagers invited to Manchester, England, by the youth movement Bnei Akiva, for a six weeks course in advanced Jewish studies. He received word from his father that the Russians were about to seize control of Hungary and he should not return.[ix] He studied philosophy at the University of London, became a vegetarian, and began having his first doubts about Orthodox Judaism. He trained as a minister at Jews College, and was ordained a Reform rabbi in 1954 by no less a mentor than Rabbi Leo Baeck, the sole surviving leader of German Jewry, who had miraculously survived the concentration camps.

He received a tempting invitation to become rabbi to a four-year-old Reform congregation in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Ungar flew to Port Elizabeth in January 1955 with his wife Corinne, and baby daughter Michelle, to a generous reception. [x] His first introduction to the peculiarities of South African practice was when he arrived at his new apartment to find an African woman sitting in the kitchen, and was told that he was expected to engage her as a maid.[xi]

He was excited by the colour, energy and exuberance of the town, delighted by the Temple that had recently been built on Upper Dickens Street, and by the generosity of the congregation itself, 250 families strong. “They were kindness itself. Invitations to dinner by the dozen, completely unwarranted gifts galore, an attitude of deference which, aged twenty five and green as I was, I found embarrassing.”[xii]

The sunshine, the fine sea views and the friendly people were the surface of a harsher political reality. The Eastern Cape had been the frontier for more than a hundred years of wars between black and white. The animosities aroused by the bloodshed turned the area into the cradle of black resistance and the African National Congress. But it was also a cradle for the most virulent strains of anti-Semitism. Two decades earlier, a local Nazi group claimed to have found in the Port Elizabeth synagogue a document outlining a Jewish plot to divide Christians and run the world. The claims had received generous coverage in the Afrikaans newspapers. [xiii] Despite being refuted in a court case, the sentiments continued to linger. Politics took a brittle form in Port Elizabeth.

Rabbi Moses Weiler, leader of the Reform movement in South Africa, flew down from Johannesburg for Ungar’s induction in March 1955. Perhaps the older man sensed some rebelliousness in the new rabbi, because his induction speech was something of a lecture on correct behaviour. As the Jewish Times reported it: “Rabbi Weiler stressed the importance of co-operation between spiritual leader and congregation. A rabbi who was not at one with his congregation, but stood apart, living in a cloud of his own, was a failure. He emphasised the virtue of possessing the courage of restraint.” Rabbi Ungar clearly interpreted this as a challenge. “He said a minister’s ultimate responsibility was to God alone, and transcended the narrow boundaries of any one congregation or religious movement.” [xiv]

Ungar started asking his congregants questions about the silent, ubiquitous but invisible, host of black servants and labourers in their employ. “How did they live? What were the relationships between them and us? Naively, I voiced such questions before my new-made friends. The response shocked me by its violence of tone. That, I was told, is a lifetime’s study. You must be born here to understand it. Foreigners can know nothing about it. Besides, it is an unsavoury topic, a communist thing to worry about.” So he chose to do his own research, making use of his “rickety old car” to “take me places”.[xv]

He found black friends. “An unforgiveable sin … they came to my home. I went to theirs. I would actually be seen going for a drive or a walk with a coloured person … More impudently still, I did invite my white and black friends together, at the same time, not necessarily having warned the white against the ploy in store for them. You should have seen them squirm when faced with the dilemma of whether to accept the outstretched hand and shake it or pretend it was not there or simply walk out in a huff! If only they ever discovered that on a weekend trip I actually shared a bed with a black man – a doctor, one of the brightest, kindest human beings I have ever met before or since …”[xvi] His friends included Govan Mbeki, later the Robben Island cellmate of Nelson Mandela, and the father to President Thabo Mbeki. Another friend was the poet Dennis Brutus, who would be jailed, then flee into exile.[xvii]

There was disapproval that the nanny was left to babysit in the living room, that the cook was paid a pound more than the local average, that the maid was given a lift by car to her family home. [xviii] Ungar raised money to offer a scholarship to a promising African student. Although Rabbi Weiler had instituted a similar bursary programme in Johannesburg, the Port Elizabeth Sisterhood resisted, urging that the money be given instead to a Jewish candidate.[xix]

Irene Zuckerman, who was a member of an amateur theatre group in Port Elizabeth along with an emerging playwright named Athol Fugard, recalls that Rabbi Ungar allowed them to secretly stage a new play at the temple one night, indeed it was the rabbi who opened the door to let them slip in. This was a bold move: the play, written by Fugard, starred two unknown black actors, John Kani and Winston Ntshona. Staging a play with black actors would have been socially unacceptable, if not illegal, in the nineteen fifties. Indeed, she recalls police prowling outside, not sure whether to break into a house of worship and arrest everyone. [xx]

The rabbi began giving sermons with a political edge. The first to cause controversy beyond the walls of the Temple, discussed the case of a local schoolboy, Stephen Ramasodi, who had won a scholarship to a prestigious American college, but was refused a passport. The sermon referred to the Torah portion of the week, in which Moses was denied entry to the Promised Land. The rabbi made parallels with Ramasodi, who had been denied his dreams, yet was innocent of any crime. The next morning’s Eastern Province Herald, under the headline “Rabbi Slates Passport Refusal to Boy”, gave generous space to the rabbi’s argument, and quoted it with some sympathy. But one sentence in particular stood out: “The harsh verdict over this young man was passed by arrogantly puffed-up little men in heartless stupidity.”[xxi]

A letter of response to the newspaper came from J Jankelson of Port Elizabeth: “I wish to express the hope that the majority of the Jewish people, local and general, will … dissociate themselves from the remarks made by that Rabbi, especially his adjectives referring to our government.”[xxii] Others joined in and soon the Afrikaans press took up the controversy. As far afield as Bloemfontein, Die Volksblad reported “Skerp Aanval deur Rabbyn op Regering. Vergelyk Naturel by Moses”. (Sharp Attack by Rabbi on Government. Compares Native to Moses.) The article described a huge row in the English press in Port Elizabeth, and anger at the phrase “arrogantly puffed-up little men”. [xxiii]

By now the rabbi was a favoured villain - particularly to the Afrikaans press - and his name would pop up in their columns regularly. His congregants became increasingly uneasy:

“And so began a series of episodes, small events, almost ridiculous to recount; yet in the context of South African tension, they were always charged with a meaning that seemed to render them instances of treason, or defiance, or insinuation. Cumulatively, they added up to a battlefront. While remaining deeply affectionate and friendly on a personal level, the Temple and its rabbi were strained in antagonism. Members were frightened for the rabbi’s sake, and his family’s and their own. He, in his turn, became more and more convinced that no religious leader is worth his salt if he shirks the responsibility of moral, if need be political, thinking and action.”[xxiv]

Ungar did, however, receive some prominent support. A letter arrived from his former mentor, Rabbi Leo Baeck. “I think you will mean something in South Africa, and open a new way … Please do not be afraid of the Big Brother; mostly the Younger Brother does carry the day. Nor be worried about polemics, polemics prove that we are alive.”[xxv]

Despite such encouragement from far away, Ungar decided to leave[xxvi]. The Temple management, despite their differences with the rabbi, were stunned when he announced his planned departure, and begged him to stay on. When it became apparent that he had made up his mind, they asked for six months’ notice to arrange for a successor. This he agreed to. [xxvii]

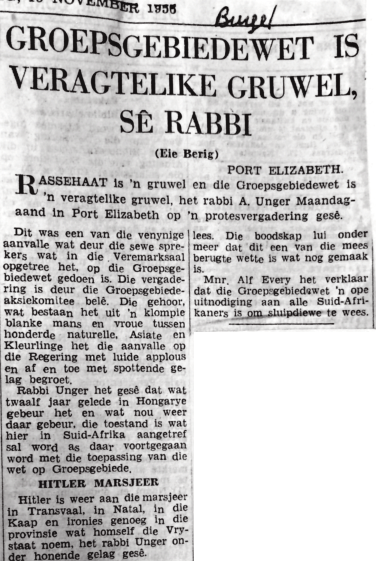

Meanwhile, the political controversies continued. The rabbi was one of seven speakers at a meeting on 13 November 1956, at the Feathermarket Hall in Port Elizabeth, which drew an audience of 750. Messages of solidarity were read out from the likes of Liberal Party leader Alan Paton, then at the height of his fame as author of “Cry the Beloved Country”. But it was Ungar’s speech which made the headlines. The Evening Post reported that he had warned white residents of the better-class suburbs of Summerstrand, Parson’s Hill and Mill Park, “who were watching and doing nothing” that retribution was bound to come over their inaction. He described how Hungarian Jews had been driven into the ghettoes by the Nazis, and how he was seeing something similar again, “under our eyes and with our connivance”.[xxviii]

A more explosive report appeared in the Afrikaans newspapers, Die Burger and Oosterlig. “Rabbi says Hitler Marches Again in South Africa.” The article began: “Race hatred is an abomination and the Group Areas Act is a despicable abomination, said Rabbi A Unger on Monday evening in Port Elizabeth at a protest meeting. This was one of the vicious attacks by seven speakers at the Feather Market Hall on the Group Areas Act … the audience, which consisted of a small group (klompie) of white men and women among hundreds of natives, Asians and Coloureds, greeted the attacks with applause and jeering laughter … Rabbi Unger said that Hitler was once again on the march in the Transvaal, Natal, the Cape and in the ironically named Free State …”[xxix]

The article drew a response in Oosterlig from “Jewish Reader” of Port Elizabeth, who was at pains to distance the Jewish community from the rabbi. “I want to state only that this rabbi represents only a very small section of the Jewish community in Port Elizabeth, namely the “Reformed Jewish Church” and that his behaviour is not approved of even by his followers … the use of the word ‘rabbi’ in your report is of course, not incorrect, yet most misleading, as the largest section of the Jewish community in South Africa do not voice Rabbi Ungar’s opinions and do not belong to his sort of church.”[xxx]

It may have been the Hitler reference that finally sealed the rabbi’s fate. On the 10th of December, the Eastern Province Herald announced prominently on its front page “City Rabbi Ordered to Leave Country”. The report said a letter from the Secretary of the Interior had been delivered to the secretary of the Temple Israel congregation, announcing that Rabbi Ungar had until 15 January 1957 to leave the country. The letter read: “By Direction of the Honourable the Minister of the Interior, I have to inform you that … you are hereby ordered to leave the Union of South Africa not later than the 15th of January 1957 … If you fail to comply with this notice, you will be guilty of an office and liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding £100, or in default of payment of the fine, to imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months.”[xxxi]

Rabbi Ungar pointed out some curious features to the deportation order. The first was that it was common knowledge, reported in the press, that the rabbi planned to leave at the end of January. The deportation order was therefore unnecessary. The second oddity was that the order was delivered first to the synagogue committee, and only followed later with a letter to the rabbi. The obvious conclusion, he said, was that the deportation was a deliberate attempt to intimidate the Jewish community “if not into active conformity, then at least into a fearsome silence”.[xxxii]

The organised Jewish community found itself with a dilemma. On the one hand, it wished to distance itself from the troublesome rabbi; on the other, it did not wish to be seen as overly supportive of a political party which had shown no great kindness to Jews. There had also, in recent months, been pressure from the Afrikaans press on an old theme, that Jews were not patriotic citizens.

In February 1955, the political correspondent of Die Transvaler wrote that “The question occurred to me whether the Jews are not abusing the safety of South Africa. They live well here and they do not complain … If they cherish love for South Africa and have ideas about South Africa, as befits South African citizens, they show it very seldom indeed.” In November, the columnist “Dawie” in Die Burger (a pen-name, usually for the editor himself), wrote: “I want to go further and ask whether the Jewish community as South Africans do not support the Government against the interference policy of the UN … Will the South African Jews use the unquestionable influence they have in Israel to present the South African case and recruit support there for South Africa just as they recruit support for Israel over here?”[xxxiii]

The Board’s discomfort can be tracked back six months earlier, to August 1956, when the chairman of the Eastern Province committee of the Jewish Board of Deputies, Mr AM Spira, wrote to the Board’s head office in Johannesburg asking for guidance as to how to deal with the increasingly embarrassing saga of Rabbi Ungar. He received in return a telegram telling him “SITUATION COMPLEX. TAKE NO ACTION”, followed by a letter from the general secretary Gus Saron, advising him: “We decided that the Board cannot and should not express opinions on political matters or matters that may be interpreted as political. On the other hand, it was felt that we have no right to interfere with the freedom of individuals to express themselves according to their own convictions; that applies also to a minister of religion. We don’t think it appropriate that our ministers should indulge in political statements, but if they feel that certain issues touch basic ethical principles or fundamental human rights, they should be free to express their views.”

Nonetheless, Saron, in his day one of the most influential leaders of the Jewish community, gave his own opinion on this: “Of course, one expects a minister, especially in the current situation, to act with a due sense of responsibility, and especially in the case of someone who is not long in the country, it would be a wise practice that he should consult with some of the more mature members of the congregation before making statements.”[xxxiv]

But in December, after Ungar’s deportation order and his remarks about the “intimidation” of the Jewish community, Spira was quick to write to the Evening Post [xxxv], arguing that the Jewish community, like other communities, consisted of individuals “of all shades of opinion” who were entitled to their own viewpoints. Likewise, government spokesmen were entitled to express their opinions about individual Jews, and these criticisms could not in any way be regarded as an attempt to intimidate the Jewish community as a whole. Rabbi Ungar spoke only for himself, “neither for his own congregation nor for South African Jewry as a whole.” Spira ended by saying that “despite Rabbi Ungar’s suggestion, the withdrawal of his temporary permit should not be, and is not regarded by the Jewish community as an attempt by the Government to intimidate such Jewish citizens of South Africa who may be critical of Government policy.”

The president of the SA Union of Progressive Judaism, J Heilbron of Durban, wrote Ungar a private letter, “the advice of a very old man with a great deal of experience in these matters … I do not doubt your honest feelings in this matter … but I do deplore the words you are reported to have used to describe the members of our Government, men with outstanding careers behind them, and men who have been appointed to act as this country’s leaders and spokesmen … You are new to this country and cannot possibly in the short time you have been here fully understand the political problems with which we have to deal in South Africa.”[xxxvi]

An editorial in the Jewish Review, the publication of the Eastern Province Jewish community, criticised the local press for making a huge “tzimmes” over the deportation issue, and said the “entire Jewish community resents Dr Ungar’s act of making a publicity stunt of it.” The writer wondered whether the rabbi had insufficient work that he could waste his time on attacking the government and said that “Dr Ungar’s departure from our country will be received by some of us with a sigh of relief”. [xxxvii]

A handful of Jews expressed support for the rabbi; none of them lived in Port Elizabeth. One Jewish writer from Cape Town complained that the leadership of Port Elizabeth’s Jewry was notoriously willing to “kow tow” to the government.[xxxviii] For the most, the local Jews were hostile. One, dispensing with the usual racial delicacies, said that the majority of whites supported segregation, and asked “who could honestly say that he would like Native neighbours in say, Mill Park or Summerstrand?”[xxxix]

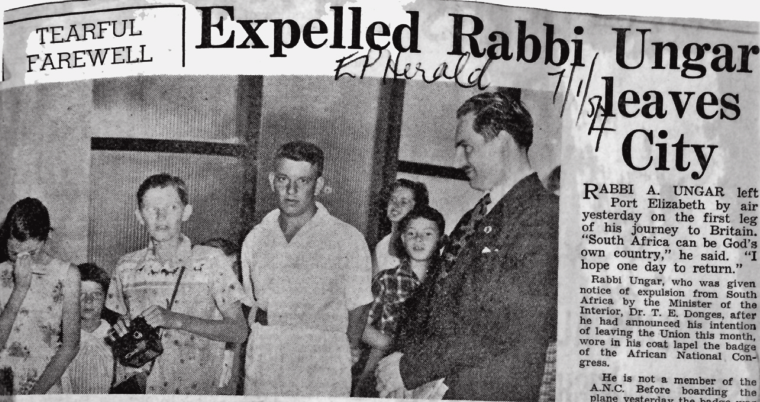

To be fair to the Temple Israel congregants, on the Sunday morning of the rabbi’s departure, almost the entire membership arrived at the airport for a farewell ceremony, where the Hebrew School children loudly sang “Haveinu Shalom Aleichem” in the departure lounge. Newspaper photographs show some of the children crying. As the rabbi himself put it: “In the eyes around me, there were relief and regret, affection and annoyance, pain and puzzled apology … A silent group of dark skinned friends stood in the opposite corner, aware that any gesture from them would land them in jail … Then a few of them, in a mad mood of daring, walked over and hastily whispered their greetings. I shook hands with them, horrifying the white onlookers by kissing my dearest friend’s wife on the cheek …”[xl]

Rabbi Ungar can recall receiving only one message of support from a Jewish religious leader. It came in the form of a cryptic telegram from the Orthodox Chief Rabbi, Louis Rabinowitz, who had hitherto been no friend of any Reform rabbi. The cable said: “RESPECTFUL SALUTATIONS - CHIEF RABBI RABINOWITZ." But although Rabinowitz made a number of political pronouncements at the time, he made no public mention of Ungar.[xli] The rabbi also received a letter of support from the last remaining Jewish member of the Senate, the Liberal Party’s vice chairman Leslie Rubin, saying that “Dr Dönges has in effect certified that you are on the side of all that is worthwhile in the values of western civilisation”.[xlii]

NOTES

[i] Lead article in the Herald Times, 14 September 1990.

[ii] Interview with Rabbi Richard Lampert, 29 January 2018.

[iii] “What will the neighbours think?” Essay in Jewish Affairs, May 1992.

[iv] Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa. David Philip Publishers, Cape Town, 2003.

[v] Milton Shain, The Roots of Anti-Semitism in South Africa, University of Witwatersrand Press, 1994; A Perfect Storm. Anti-Semitism in South Africa 1930-1948. Jonathan Ball, 2015.

[vi] In his submissions to the Truth Commission, Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris covered many of these issues with an admirable honesty. (Reconciliation – A Jewish View. Submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, January 1997).

[vii] Personal communication from Rabbi Ungar, courtesy of Judy Ungar. July 2017.

[viii] According to Ungar’s own two-part account of Hungary under Nazi rule, in the US publication, Jewish Spectator. (Hungarian Memories, June and October 1959.) Also, New Jersey Jewish Standard, op cit.

[ix] New Jersey Jewish Standard, op cit.

[x] Personal communication from Rabbi Ungar; Jewish Spectator, op cit; New Jersey Jewish Standard, op cit. There was a competing invitation from Australia, but South Africa seemed closer to Europe.

[xi] New Jersey Jewish Standard, op cit.

[xii] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit.

[xiii] Milton Shain, A Perfect Storm. Anti-Semitism in South Africa 1930-1948. Jonathan Ball, 2015. Op cit.

[xiv] SA Jewish Times, 1 April 1955.

[xv] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit.

[xvi] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit

[xvii] Personal communication from Rabbi Ungar, July 2017.

[xviii] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit. Another cause for surprise was that he took over some of the babysitting and bathing so that his wife could go out. (Eastern Province Herald, cutting in Ungar personal papers.)

[xix] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit. The idea was regarded as too “bolshie”, or communist.

[xx] Personal correspondence with Irene Zuckerman, May 2020.

[xxi] Eastern Province Herald, 30 July 1955. “A young man, almost a child, had his dreams of entering what, in his circumstances, must be the nearest equivalent of the Promised Land, most cruelly shattered. Moses was old and had learnt to bear disappointment, but youth is naïve and trusting”.

[xxii] Eastern Province Herald, 3 August 1955

[xxiii] Die Volksblad, 8 August 1955. (Press cutting in Jewish Board of Deputies archives, Johannesburg.)

[xxiv] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit. But the rabbi did get some support. “Others pressed my hand. ‘Thank God, at last somebody says what must be said.’ Many more murmured, ‘Yes of course you are right, but is it safe? Think of the consequences, for yourself, for all of us.’ ” (Jewish Spectator, My Ten Synagogues, op cit.)

[xxv] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit.

[xxvi] An old contact in London had offered him a plum post at an English synagogue.

[xxvii] No successor had been found by the time the six months was up.

[xxviii] “A Price to be Paid. Warning to PE Whites.” Evening Post, 13 November 1956.

[xxix] Oosterlig and Die Burger (identical text) 13 November, 1956. (My translation from Afrikaans.)

[xxx] Oosterlig, 23 November 1956.

[xxxi] The Reconstructionist, 18 March 1960, op cit. A slightly different wording in the notice to the Temple Israel secretary said that the rabbi’s temporary residence permit had been withdrawn.

[xxxii] Evening Post, 17 December 1956.

[xxxiii] The Israel reference relates to Israel joining in a United Nations vote condemning apartheid.

[xxxiv] Letter from GS (Gus Saron) to “Bobby” (AM Spira), 1 August 1956. Board of Deputies archives, Johannesburg.

[xxxv] Letter to Evening Post, 14 December 1956. Spira was responding to Ungar’s initial claims about “intimidation”, made immediately after the deportation order was issued.

[xxxvi] Letter in the Rochlin Archives, Jewish Board of Deputies (Courtesy Professor Adam Mendelsohn).

[xxxvii] Jewish Review, December 1956. (Jewish Board of Deputies archives, Johannesburg).

[xxxviii] Cape Town Jewish Citizen in Evening Post, 22 December 1956. “I have been shaken by the reaction (or lack of it) by Port Elizabeth’s Jewry” adding “no man who supports the racialist policies of this government has the right to call himself a Jew”.

[xxxix] Immigrant of Walmer, Evening Post, 11 December 1956.”We should always be ready to give a fitting reply to any foreign busy-body offering cheap criticism.”

[xl] The Reconstructionist, 1 April 1960, op cit. Rabbi Ungar would spend 44 years as rabbi

[xli] Personal communication from Rabbi Ungar, 1 December 2017, op cit. Rabinowitz, who tended to come out fighting on almost any topic, spoke out more strongly against apartheid than most other rabbis of his generation, as Shimoni has shown. (Shimoni, op cit.) But Rabinowitz too, had plans to leave the country.

[xlii] The Reconstructionist, 1 April 1960, op cit. Until the arrival of Helen Suzman, Rubin was the most outspoken Jew in parliament.